Now I finally have my house back again, I’m seriously overdue a little retro gaming to make up for the enforced 7 month hiatus. This should mean a load more posts in the near future. Above all else, I wanted to have a go on that relatively recently acquired Tandy 1000 EX.

Since posting about that previously, I managed to find a memory expansion for it bringing the RAM up to the giddy heights of 640K. It also adds a DMA controller making it slightly more PC compatible and in theory speeding up load times off floppy. The Tandy has an interesting expansion system where a slot opens up in top of the machine and expansions have to be slotted in on top of each other. This means you have to unscrew the blank plates from all 3 before you can put a card in the bottom. Lining up the slots proved quite tricky since I had absolutely no way of telling where they are in relation to each other. This system is entirely unique to a couple of specific models in the Tandy line making these cards difficult to locate even if the demand isn’t exactly sky high.

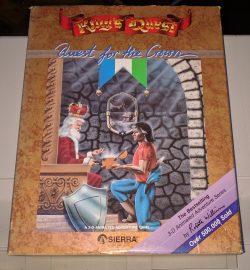

Having got that working (and even though I don’t strictly need the extra memory to play it), the first game had to be Sierra’s King’s Quest.

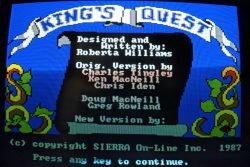

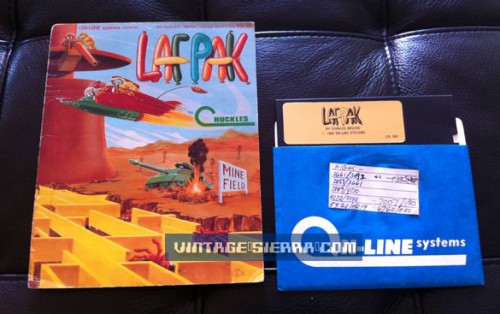

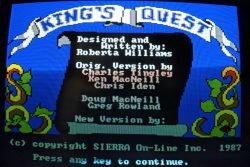

Sierra pioneered the graphical adventure game starting out with Mystery House on the Apple II all the way back in 1980 and continuing to release ever more ambitious titles throughout the early 80’s. When IBM wanted some software to show off the gaming capabilities of their forthcoming PC-Jr, Sierra were certainly one of the obvious choices to create it and the result of that deal was King’s Quest.

IBM’s attempt to enter the home PC market with the PC-Jr would prove to be a dismal failure, largely due to the price point and the famously horrific keyboard. King’s Quest on the other hand would become a staple of PC gaming, managing nearly as many games it’s in main canon as Ultima. Despite the nature of that IBM contract, Sierra were wise enough not to put all their eggs in one basket. They created a whole new engine (AGI) which ran the game on a virtual machine and allowed for easy porting to other platforms. The PC-Jr format would still see much success ultimately in the form of Tandy’s clone which fixed most things IBM had got wrong the first time around.

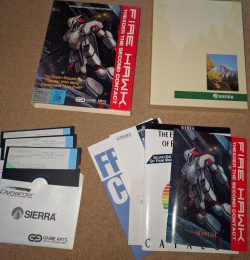

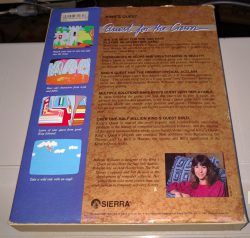

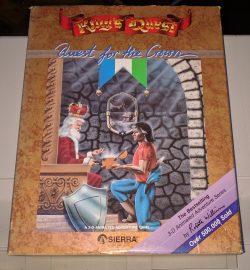

My copy of King’s Quest isn’t the original release which was a PC-Booter but it is the one I bought back in the late 80’s as a trilogy pack with the first 3 entries in the series. This later version used a more advanced AGI engine (requiring twice the memory), had quite different box art and most importantly for me at the time I played it came on both disk formats and not just 5.25’s.

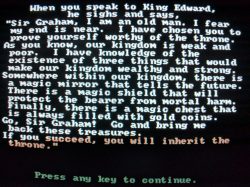

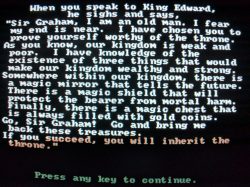

The box isn’t exactly stuffed full of goodies but does have quite a nice manual with an embossed King’s Quest logo and the story that sets up the game. All the King’s Quest games are based on fairy tales and the manual is very much written in this vein. In brief, King Edward (the ruler of Daventry), manages to give away the Kingdom’s greatest treasures which are a shield that makes his armies invincible, a chest with everlasting treasure, and a mirror that tells him the future. This is clearly why we shouldn’t have a hereditary system of rulership. It’s about what you should expect when you name someone after a potato I suppose. In the game, I’ll be playing Sir Graham, bravest of King Edward’s knights, who has to sort this mess out.

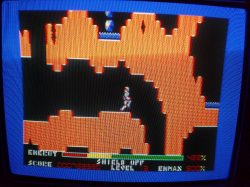

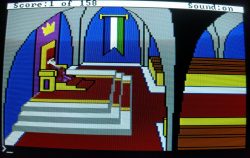

The game starts with a rendition of Greensleeves (apparently not in the original booter version) and then I take over control of Sir Graham. This is a traditional text adventure game in one sense with a prompt at the bottom to type commands. The big innovation was being able to walk Graham around the world with the cursor keys. This added a minuscule amount of arcade gaming to the experience avoiding all the monsters roaming around the countryside. We hadn’t got as far as pointing and clicking yet, but this was the dawn of that style of adventure gaming.

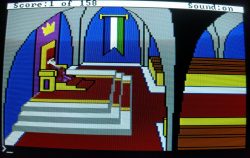

Job #1 in this game is to go and see King Edward who despite the apparent poverty he has put Daventry into, still lives in a castle so large it won’t fit on one screen of the game. He’s kept safe from marauding peasants seeking social justice by a crocodile infested moat which probably explains the sparsely populated nature of his Kingdom.

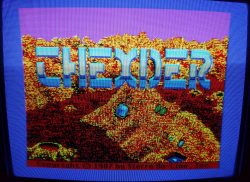

Graphically, the game looked impressive back in 1984 despite only being in an unusual 160×200 resolution when the Tandy was capable of the full 320×200. I didn’t realize it when I first played these games but the backgrounds are entirely made up of filled polygons and on the booter version, you can actually see these being drawn to the screen. This saved on disk space and kept loading times to a minimum.

Speaking of which, I played this off the original 5.25 disks and the loading times really aren’t too bad considering the hardware. They would have seemed positively speedy at the time with 2-3 seconds to load each new room. What I didn’t like was having to swap disks to save my game.Many of the screens have random monsters that mean instant death if they catch you. They aren’t capable of chasing between screens at least so you soon learn to stay near the edges of screens in this game and save often.

I’m getting ahead of myself though. Before I can explore the countryside, I have to go and get my quest from King Edward. I have to retrieve the 3 missing treasures and in return will get to be King.

Gameplay in King’s Quest is extremely non-linear and these treasures can be obtained in any order. There are usually several solutions to every puzzle with some solutions worth more points than others (non-violent solutions usually being the more valuable).The main world consists of roughly 20-30 screens in a grid that rolls back around to the opposite side at the edges, and there are further sub locations, inside houses, below ground, etc most of which are on the second of the two floppy disks.

Apart from the 3 main treasures, various other valuable items are scattered about which can be gathered for points. These tend to be hidden in tree stumps or logs and the like. I don’t think I’ve ever managed full points in this game so there must be one somewhere I’ve never found.

The first main treasure I stumble into is the magic mirror, which is through a cave at the bottom of a well. It’s guarded by a dragon who I disable by throwing a bucket of water in its mouth.

The world map is large enough that I never really did learn my way around. I do notice that some of the screens in the game appear to be a whole lot better drawn than others as I roam around Daventry. E.g. the bush on the right of the screen above looks like something I might come up with, were I to try to draw the outline of the UK with a ball mouse that hadn’t been cleaned out for 10 years. It’s a completely nondescript room with nothing whatsoever to do on it but you’d think they could have tried a little harder

The most infamous puzzle in Kings Quest involves guessing the name of a dwarf who lives on a little island near the castle. You get three goes and the only clue is a note in an unrelated part of the map which says “Sometimes it is wise to think backwards”. I only solved this one when I got the Official Book of King’s Quest which didn’t give the answer but did have a crossword puzzle that gave me enough of a clue. I won’t give away the answer but suffice to say, not many people would have guessed it and the puzzle isn’t exactly fair.

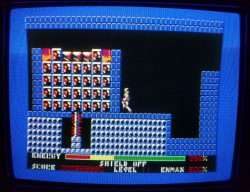

The game can be completed without solving this to be fair and the only reward other than some points is an excruciating climb up a beanstalk with little guidance on exactly where is safe to tread. It took much disk swapping and reloading before I made it up to the clouds. Once there I’m set upon by a giant but thanks to the games limited pathfinding capabilities, it’s possible to position myself behind a tree and avoid him. Eventually, he gets fed up, falls asleep and I pinch the chest he was holding which is the 2nd missing treasure.

Curiously on the Tandy, there is a snoring sound effect when the giant falls asleep. It’s not exactly impressive by modern standards but the noise channel on the Tandy is definitely ahead of what I’d have got from the PC speaker in this game. The use of music and sound is very limited though with little more than a death theme and a couple of seconds of warning music when a monster shows up.

The final treasure is under the ground. Reaching this place requires finding a passing eagle who only occasionally appears on one of the games screens, and then using the games “jump” key (which is entirely useless otherwise) at just the right time and location to catch onto the eagles claws. I knew what to do through bitter experience the first time around but how I guessed it as a kid, I have no idea. I expect trial, error and a whole lot of free time.

At any rate, this eagle flies me to a little island, I drop through a hole in the ground and thanks to a fiddle I took from the only two people left in Daventry I’m able to make all the leprechauns that live down here dance away and retrieve the final missing treasure.

All that is left to do is head back to the castle (which took me at least 10 minutes to locate again). King Edward grants me the throne before keeling over dead. Showing all due respect to the ex-monarch, Graham heads straight for the throne to claim his prize while Edward’s body still lies on the ground. There is one final rendition of Greensleeves and some brief credits.

I was reminded a lot of Zork playing this again all these years later in some ways. King’s Quest is a very traditional treasure search as was so common in early interactive fiction. It doesn’t have the puzzles or complexity of Zork of course.

I usually ask myself if a game has held up when I finish it but I’m unconvinced that King’s Quest was all that much of a game in the first place. It’s extremely brief and without any particularly memorable puzzles or plot. Comparing it to contemporary offerings from Infocom such as Hitchhikers Guide To The Galaxy, it’s ridiculously simplistic. Compared to most other publishers of the time, it holds up far better I suppose with the added attraction of the graphics.

Sierra’s more forward thinking approach would ultimately be proved correct a couple of years later as the traditional IF market died off and the graphical adventure game started to come into its own. In the meanwhile, King’s Quest wasn’t without its charms but Sierra would do far better with this engine in later efforts. The King’s Quest series is no doubt aimed at a young audience and as an introduction to adventure games this serves quite well with the open structure limiting dead ends and multiple solutions offering more chances to get past each puzzle. I’m still not sure it’s a title I could honestly recommend to a new player with so many better adventure games available. It did get a remake a few years later and then a fan remake some years after that, both of which I may well look at eventually.

That will have to wait as in the next post, I’ll be almost getting back on topic and looking at a curious entry in Warren Spector’s early career.